08 Jul «Tell me how you accelerate and I’ll tell you who you are»

The physical-tactical profile of each position in LALIGA

Introduction: If you don’t measure it, can you train it?

In professional football, statistics rule. Total distance covered, top speed, number of sprints… But what about the actions that decide matches and never reach the classic thresholds? What if the most demanding effort isn’t the most visible? How many tactical decisions, successful presses, or match-winning runs begin with an intense but short acceleration, far from the GPS spotlight?

From the Football Intelligence area at LALIGA, and in collaboration with researchers from the Universidad Rey Juan Carlos and the Universidad Miguel Hernández de Elche, we recently published a study that addresses this very question.

The article, titled “Locomotor characteristics of intense accelerations according to the playing position in top Spanish football teams during competition”, was published in Biology of Sport and is openly available here:

? https://doi.org/10.5114/biolsport.2025.151652

Based on that scientific foundation, we’ve gone one step further. In this extended article, we integrate the findings from the original research with real match data from the 2024/25 season, introducing an additional layer of analysis: the tactical context in which maximum accelerations occur.

The goal: to understand what accelerations can reveal about the physical and tactical identity of each position. Not as a static image, but as a dynamic X-ray of the game.

Why focus on acceleration?

Most match-defining actions occur at submaximal speeds, but with high neuromuscular demand: pressing, recovering, attacking space, tracking back… They all have one thing in common: intentional acceleration.

The original study introduced a new approach. Instead of using fixed speed thresholds (>3 m/s²), it focused on accelerations that exceeded 50% of each player’s individual acceleration–speed profile. In doing so, it captured meaningful efforts regardless of the player’s position or running style.

And the findings were clear:

- Forwards (FW) recorded the highest peak and average acceleration values.

- Wingers (W) hit the highest top speeds and distances.

- Midfielders (CM, AM) accelerated more frequently, but with lower intensity.

- Centre backs (CD) posted the lowest acceleration values overall.

Familiar? Perhaps. But now things get even more interesting.

What happens when we add tactical context?

Using an independent dataset —with players who accumulated at least 400 minutes in LALIGA 2024/25— we analysed maximum acceleration values within different tactical contexts: Build Up, Counter Attack, Opposition Creation, Transitions, and more.

The question: do the scientific findings hold up under tactical scrutiny?

The data speaks for itself.

Offensive roles still dominate

In phases such as Counter Attack, Creation, or Block Shift, forwards (FW) and attacking midfielders (AM) maintain their dominance in terms of peak acceleration.

- In Counter Attack, forwards average 3.50 m/s², far above centre backs (2.65).

- In Creation, AMs and full backs hit 4.35–4.39 m/s², outperforming CMs and CDs.

- In Build Up, full backs lead with 5.39 m/s², closely followed by AMs and FWs.

What does this suggest? That attacking roles—especially those focused on breaking lines or running into space—demand the most explosive efforts, even when raw match data may not show it.

Defensive roles accelerate… backwards

In contexts such as Block Shift or Opposition Build Up, defenders (CD and FB) post high acceleration values, but in different directions and with different tactical intentions. The study already indicated that full backs operate with a mixed profile—offensive and defensive.

Adding tactical context confirms this: full backs register high acceleration peaks in both possession and non-possession phases, indicating constant transitions. Are we training these dual roles with the same precision we apply to offensive sprint work?

Midfielders: everywhere and nowhere

Central midfielders (CM) show high frequency but moderate intensity. They’re required to accelerate often, but usually from moderate speeds or within transitions rather than deep runs. This naturally lowers their peak acceleration but not their physiological demand. The takeaway: we must read these profiles physiologically, not just biomechanically.

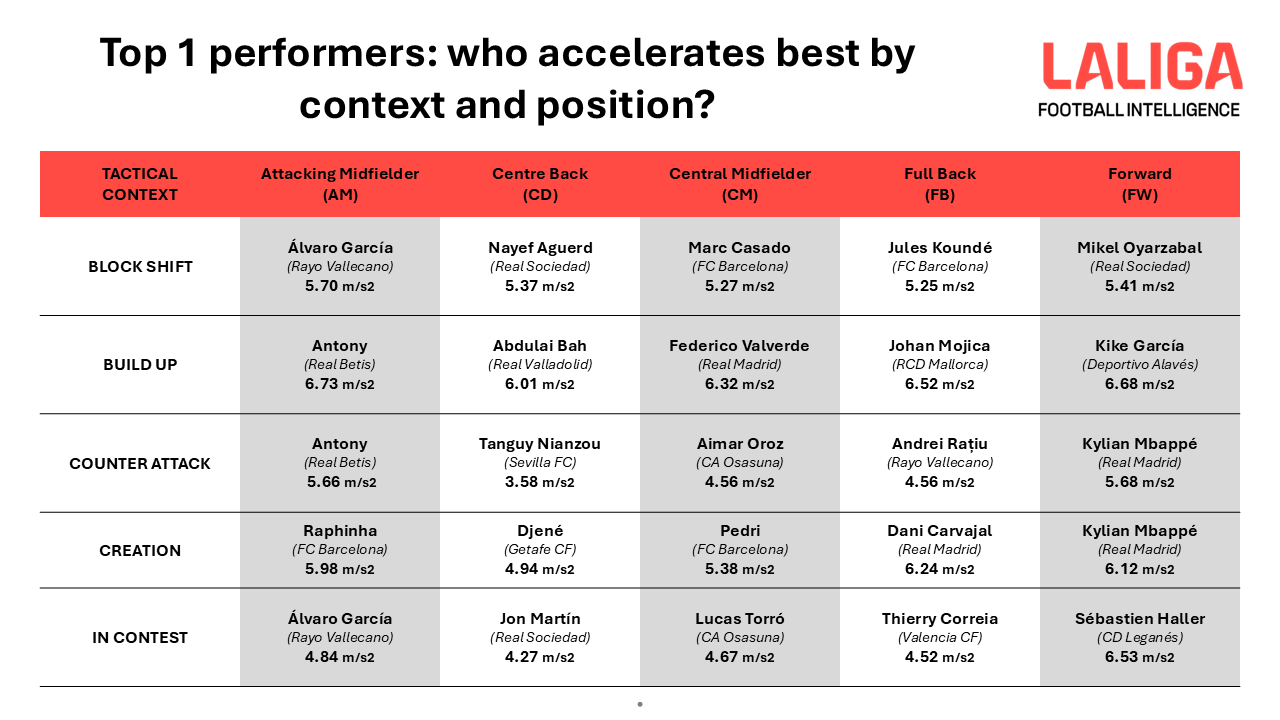

Top 1 performers: who accelerates best by context and position?

Focusing only on players with at least 400 minutes played, we identified the peak performers in terms of maximum acceleration by context and positional group. Each entry below represents the highest recorded acceleration value for that position in that specific tactical phase:

| Tactical Context | AM | CD | CM | FB | FW |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Block Shift | Álvaro García (Rayo Vallecano) – 5.70 m/s2 | Nayef Aguerd (Real Sociedad) – 5.37 m/s2 | Marc Casado (FC Barcelona) – 5.27 m/s2 | Jules Koundé (FC Barcelona) – 5.25 m/s2 | Mikel Oyarzabal (Real Sociedad) – 5.41 m/s2 |

| Build Up | Antony (Real Betis) – 6.73m/s2 | Abdulai Bah (Real Valladolid) – 6.01 m/s2 | Federico Valverde (Real Madrid) – 6.32 m/s2 | Johan Mojica (RCD Mallorca) – 6.52 m/s2 | Kike García (Deportivo Alavés) – 6.68 m/s2 |

| Counter Attack | Antony (Real Betis) – 5.66 m/s2 | Tanguy Nianzou (Sevilla FC) – 3.58 m/s2 | Aimar Oroz (CA Osasuna) – 4.56 m/s2 | Andrei Rațiu (Rayo Vallecano) – 4.56 m/s2 | Kylian Mbappé (Real Madrid) – 5.68 m/s2 |

| Creation | Raphinha (FC Barcelona) – 5.98 m/s2 | Djené (Getafe CF) – 4.94 m/s2 | Pedri (FC Barcelona) – 5.38 m/s2 | Dani Carvajal (Real Madrid) – 6.24 m/s2 | Kylian Mbappé (Real Madrid) – 6.12 m/s2 |

| In Contest | Álvaro García (Rayo Vallecano) – 4.84 m/s2 | Jon Martín (Real Sociedad) – 4.27m/s2 | Lucas Torró (CA Osasuna) – 4.67 m/s2 | Thierry Correia (Valencia CF) – 4.52 m/s2 | Sébastien Haller (CD Leganés) – 6.53 m/s2 |

What does this mean for training?

1. Design drills that respect positional specificity

- FWs and AMs should train high-intensity accelerations in open-space contexts (Creation, Counter Attack).

- CDs and CMs benefit from short, reactive drills starting from low speeds (Block Shift, Defensive Transition).

- FBs must be trained for both forward surges and backward recoveries.

2. Don’t train acceleration without context

The same acceleration number can mean very different things. A raw figure of 3.9 m/s² tells us nothing if we don’t know whether it was an attacking run, a retreat, or a cover.

3. Measure, but interpret

Acceleration metrics—especially in context—can provide more relevant insights into actual match load than distance or sprint totals alone.

And you—how are you training accelerations?

- Do your drills simulate the contexts in which accelerations actually occur?

- Do you know the average starting speed your players have before accelerating?

- Should your full back accelerate like your forward? Or differently?

Final thought: acceleration as a positional fingerprint

Each position has its own acceleration DNA. It’s not just about how often or how fast a player accelerates—but when, how, and why they do it.

That distinction is what separates generic conditioning from performance-specific training.

This fusion of published research and real, contextualised data reveals that even at the micro level of physical expression—acceleration—the game remains the ultimate lens. And training without understanding it… is just running without direction.