04 Sep Ball Possession vs Physical Performance: the real trade‑offs coaches must manage

What LaLiga data really says about ball possession and physical demands

A real sideline question

It’s Friday. You’re finalising tomorrow’s plan. One assistant argues for 60% possession to control the game; another wants a more direct, pressing approach. Then the physio asks: “What does that do to our players’ legs in minute 75?”

This post translates a series of peer‑reviewed studies conducted by the Football Intelligence & Performance Department at LALIGA into practical guidance for coaches, physical trainers and performance analysts. The message is simple but counterintuitive: not all running is created equal—with the ball matters more than how much you run.

Below, we keep the scientific backbone (Introduction → Methods → Results → Conclusions) but tell it as a coach’s story—actionable, testable, grounded in data.

Introduction — The possession paradox

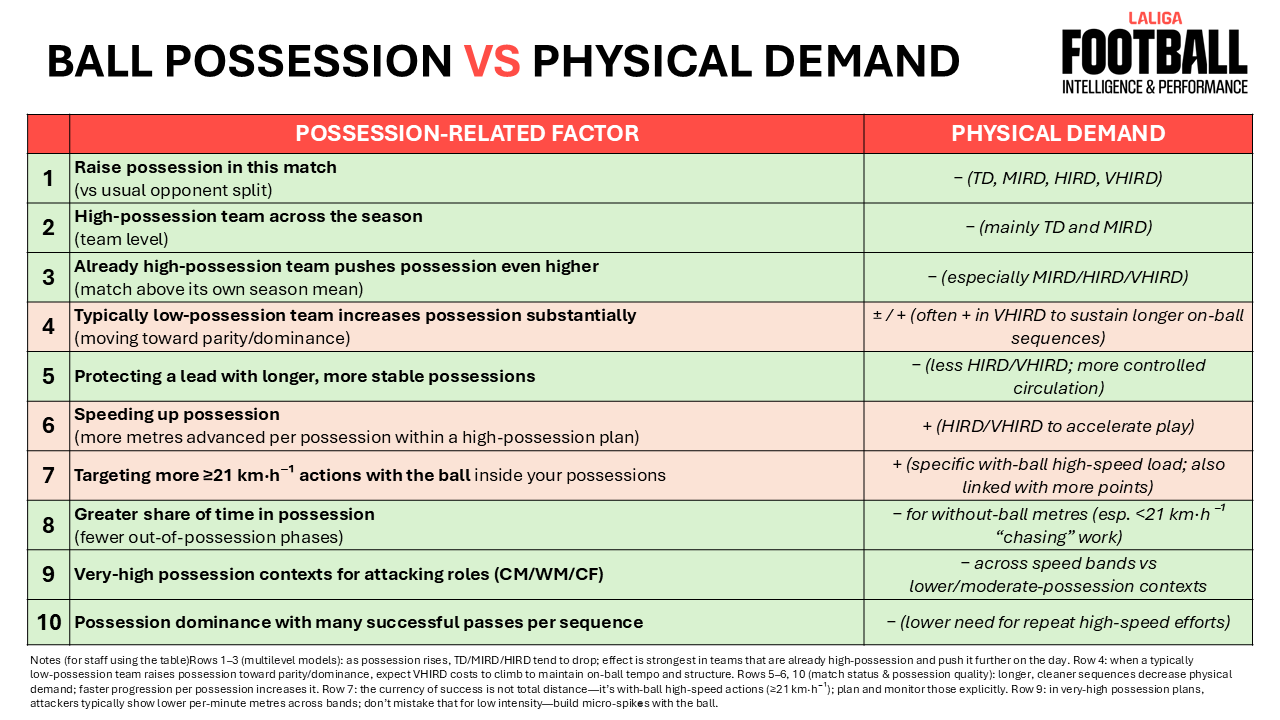

A common assumption in football is that “working harder” (i.e., running more) increases your chances to win. Our multi‑season analyses challenge, refine, and—crucially—contextualise that idea:

- Raising possession typically reduces total and high‑intensity distances both within a match and across a season profile. Yet the quality of those metres—and whether they are with the ball—changes the performance picture.

- Successful teams don’t necessarily run more overall; they run better with the ball, especially at higher speeds. That specific behaviour is a stronger marker of success than total distance alone.

- Match status modulates possession behaviour: when winning, teams tend to hold longer possessions and complete more passes, while teams that are losing push the ball forward faster and cover more metres per possession.

Coaching takeaway: treat possession not as a philosophical identity but as a workload design lever. The way you organise possession changes the type and intensity of the running your players do.

Methods — What we measured and why it matters to you

Across multiple peer‑reviewed studies, we analysed LaLiga match data obtained with the official Mediacoach® multi‑camera tracking system (25 Hz) and validated procedures. We combined two complementary angles:

- Multi‑season, multi‑level models (team level across seasons and match level within a season) to quantify how possession affects distances at specific speed zones:

- Total distance (TD)

- 14.1–21.0 km·h⁻¹ (Medium‑Intensity Running Distance, MIRD)

- 21.1–24.0 km·h⁻¹ (High‑Intensity Running Distance, HIRD)

- 24.1 km·h⁻¹ (Very High‑Intensity Running Distance, VHIRD)

- With‑ball vs without‑ball lens to separate what kind of running associates with success:

- Distances at ≥21 km·h⁻¹ with possession

- Distances at ≥21 km·h⁻¹ without possession

- End‑of‑season points and ranking as outcomes

We also examined how possession profiles (very high, high, low, very low) interact with playing position and effective playing time—to ensure physical loads are interpreted against the time when the ball is actually in play.

Results — What changes on the pitch when possession changes

1) More possession → fewer metres (but smarter metres)

- At match level: When a team’s possession increases in a given game, total and high‑intensity distances drop. This negative relationship is particularly strong for teams that already have a high average possession across the season (cross‑level interaction). In those squads, pushing possession above their norm further reduces MIRD/HIRD/VHIRD—a sign of efficient, coordinated circulation that lowers chasing and recovery runs.

- At team (season) level: Squads with higher average possession across the season tend to cover less total and medium‑intensity distance. However, they still need select bursts of very‑high intensity to accelerate the game when it matters.

Coaching application: possession‑dominant teams should train efficiency and acceleration timing, not chronic volume. Build the ability to “spike” at the right moments.

2) Success is tied to with‑ball high‑speed actions

- Across four seasons, the single best running predictor of points was distance at ≥21 km·h⁻¹ with the ball—not total distance. Champions even tended to run less overall than other teams, but more with the ball, especially at higher speeds. Combined running metrics explained ~38% of variance in points; the with‑ball component drove the lion’s share.

Coaching application: design drills that reward high‑speed actions with the ball (break‑line carries, fast overlaps in possession, third‑man runs to receive beyond pressure). Measure and monitor those efforts explicitly.

3) Position‑specific shifts under different possession styles

- Very‑high possession teams: attackers (CM, wide MF, forwards) covered fewer metres per minute at every speed band than their counterparts in lower‑possession teams. Defenders in very‑low possession teams covered less overall—consistent with deeper blocks and fewer progressive actions—while external defenders in low‑possession settings showed especially reduced high‑speed work. Effective playing time was also subtly different across possession contexts.

Coaching application:

- Forwards in high‑possession teams require short, explosive with‑ball accelerations and micro‑positioning more than raw volume.

- External defenders in low‑possession or deep‑block plans need targeted transition capacity (longer high‑speed recoveries and support runs).

- Always interpret loads by role and possession context rather than global team totals.

4) Match status changes how teams use possession

- When winning, teams tended to have longer possessions and more successful passes; when losing, they advanced more metres per possession (faster, more vertical sequences). These context shifts align with intuitive strategies—but quantifying them helps you plan the next phase of play and substitutions objectively.

Coaching application: train scenario‑switching: “protect a lead via stable possession” vs “chase a goal with accelerated progression,” and be explicit about how each scenario re‑shapes physical outputs.

Conclusions — What this evidence confirms, challenges, and refines

What it confirms

- Possession style shapes physical demands; there is no universal “workload” profile.

- Running with the ball—especially at high speeds—is a signature of competitive success.

What it challenges

- The belief that more kilometres = better performance. Champions can cover less total distance and still be more effective through with‑ball high‑speed actions.

What it refines

- High possession is not “easier” per se; it re‑allocates the work: fewer chase metres, more timed accelerations with the ball; different positional patterns of demand; subtle changes in effective playing time.

From evidence to training: practical menus you can use tomorrow

A) If you expect to dominate possession

- Design: 7v7+3/8v8+2 with directional goals; constraints to trigger ≥21 km·h⁻¹ with‑ball carries (e.g., 5s “go” window after a third‑man bounce).

- Metrics to track:

- Count of with‑ball high‑speed efforts per role (≥21 km·h⁻¹).

- Entry timing into the last third after regain (seconds).

- Accelerations that start with the ball vs without.

- Micro‑dosing speed: 2–3 micro‑reps of 3–5 s with‑ball sprints inside the tactical game to avoid chronic volume creep.

B) If you expect to cede possession and press

- Design: pressing circuits with longer recoveries for external defenders and wingers (30–40 m repeat efforts), paired with counter‑attack finishes.

- Metrics to track:

- VHIRD in out‑of‑possession phases (are you asking for more than your baseline can support?).

- Regain‑to‑shot time and metres advanced per possession when chasing the game.

C) If you expect status shifts (leading/trailing within the game)

- Train both scripts: “Protect the lead” (stable circulation, lower HIRD/VHIRD) vs “Chase the equaliser” (faster progression, higher metres advanced per possession).

- Substitution logic: prefer with‑ball speed reserves (wide MF/FB/9) when you need to create changes, because those efforts associate best with points.

Reading your data on Monday: three non‑negotiables

- Split with‑ball vs without‑ball. Total distance hides the signal; success is tied to with‑ball high‑speed.

- Benchmark against your own possession profile. A “high TD” day could be normal for a low‑possession plan, but a warning flag for high‑possession teams.

- Factor match status and role. Expect different demands when protecting vs chasing; defend differently by position under low possession.

Limitations (what to keep in mind without losing the message)

- Speed bands and categorisation: some analyses used broad thresholds; finer bands may add nuance without changing the core result: with‑ball ≥21 km·h⁻¹ is the critical signal.

- Situational variables (opponent quality, venue, scoreline) are imperfectly controlled in some models; still, multi‑level and multi‑season designs stabilise estimates and align with on‑pitch logic.

- League specificity: findings are from LaLiga; other leagues may differ in style, but the principle “with‑ball speed over total volume” has replicated elsewhere.

What this means for your programme

Treat the pitch as a living laboratory. Use possession as a dial to shape physical outputs; prioritise with‑ball speed as a performance currency; and test your assumptions weekly:

- If we raised possession by 5–10% this week, did our with‑ball ≥21 km·h⁻¹ actions rise or fall?

- When we led after HT, did our possession quality change (longer sequences, more successful passes), and did we protect the right players for late with‑ball bursts?

- Are our role‑specific loads consistent with our style? (e.g., low with‑ball speed in wide players of a high‑possession team = red flag).

References

- Brito Souza, D., López‑Del Campo, R., Blanco‑Pita, H., Resta, R., & Del Coso, J. (2020). Association of match running performance with and without ball possession to football performance. International Journal of Performance Analysis in Sport. (https://doi.org/10.1080/24748668.2020.1762279)

- García‑Calvo, T., Ponce‑Bordón, J. C., Leo, F. M., López‑Del Campo, R., Nevado‑Garrosa, F., & Pulido, J. J. (2022). How does ball possession affect the physical demands in Spanish LaLiga? A multilevel approach. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport. (https://doi.org/10.1080/02701367.2022.2072798)

- Lobo‑Triviño, D., Ponce‑Bordón, J. C., Llanos‑Muñoz, R., López‑Del Campo, R., & López‑Gajardo, M. A. (2023). ¿Influye el resultado final sobre variables relacionadas con la posesión de balón en LaLiga Santander? Revista Española de Educación Física y Deportes (REEFD), 437(4). (https://doi.org/10.55166/reefd.v437i4.1102)

- Lorenzo‑Martínez, M., Kalén, A., Rey, E., López‑Del Campo, R., Resta, R., & Lago‑Peñas, C. (2020). Do elite soccer players cover less distance when their team spent more time in possession of the ball? Science and Medicine in Football. (https://doi.org/10.1080/24733938.2020.1853211)