28 Abr Acceleration-speed profiles in LaLiga: the influence of initial running speed and differences between positional roles in elite football players

Modern football is not decided by how fast players run, but by how they accelerate. This study changes how acceleration should be understood, monitored, and trained in elite football.

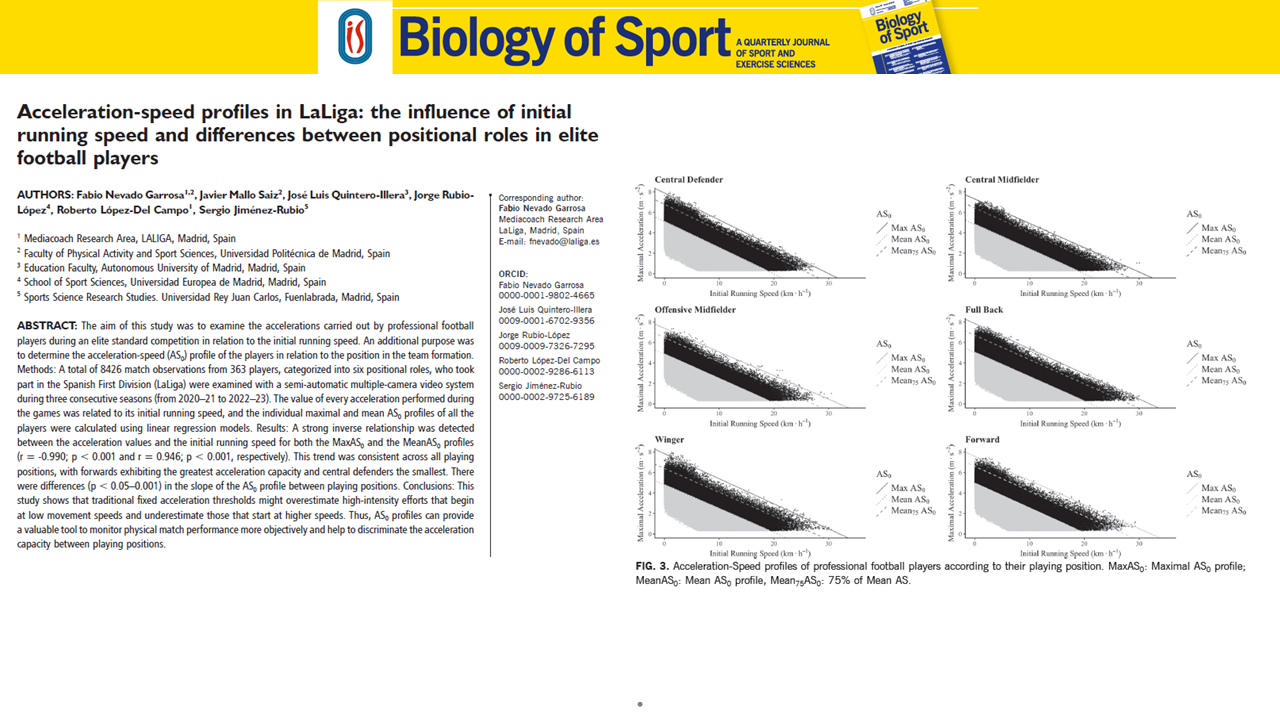

The key message is simple. Acceleration cannot be separated from the speed at which it starts. The faster a player is already moving, the lower his ability to further accelerate. This relationship is not weak. It explains more than 90% of all acceleration values observed in LaLiga matches across three full seasons.

This matters because most performance departments still use fixed acceleration thresholds. Values like 3 m·s⁻² are commonly labelled as “high-intensity”. The data from LaLiga show why this is misleading. Almost all accelerations that exceed these thresholds start from very low speeds. More than 90% of accelerations above 3 m·s⁻² begin below 7 km·h⁻¹.

In real match situations, many of the most demanding actions start at higher running speeds. Pressing while already moving. Defensive recovery runs. Offensive movements attacking space. These actions often fail to cross fixed acceleration thresholds, yet they place a high mechanical and neuromuscular load on the player. When only absolute thresholds are used, these efforts disappear from the analysis.

The acceleration–speed profile solves this problem.

Instead of asking “how big was the acceleration?”, the profile asks “how big was the acceleration relative to the speed at which it started?”. This creates a clear and objective picture of how demanding an action truly is.

For practitioners, this has direct consequences for training design and load monitoring. High-intensity acceleration is not just about explosive starts from standing positions. It is also about the ability to accelerate when already running. Ignoring this leads to an underestimation of match demands and a mismatch between training and competition.

The study also confirms strong positional differences. Forwards show the greatest acceleration capacity across the speed spectrum. Central defenders show the lowest. These differences are consistent and stable across seasons. This reinforces the need for position-specific benchmarks rather than universal thresholds applied to all players.

Interestingly, some positions share similar maximum acceleration potential but differ in how well they maintain acceleration as speed increases. This means two players can look similar if you only observe peak values, but very different when match context is considered. This insight is critical when profiling players, individualising conditioning work, or interpreting match loads.

Another major advantage of the acceleration–speed profile is practicality. It can be calculated directly from match or training tracking data. No additional testing is required. No maximal sprint tests. No laboratory conditions. This makes it suitable for continuous monitoring throughout the season.

From a performance perspective, this approach allows staff to better understand why a player feels fatigued despite “low” acceleration counts. From a prevention perspective, it helps identify hidden mechanical load that traditional metrics miss. From a coaching perspective, it supports more realistic drill design that reflects true match demands.

The main takeaway is clear. Acceleration should never be analysed in isolation. Initial running speed changes everything. When speed and acceleration are combined, the interpretation of match demands becomes more accurate, more individual, and more useful for decision-making in elite football.