31 Dic Does the final result influence ball possession-related variables in LaLiga Santander?

Ball possession is not a static concept. It changes with the score. It changes with context. And it changes with intent. This study analysed every single match of the 2019/20 LaLiga season to understand how teams actually use possession depending on whether they are winning, drawing, or losing.

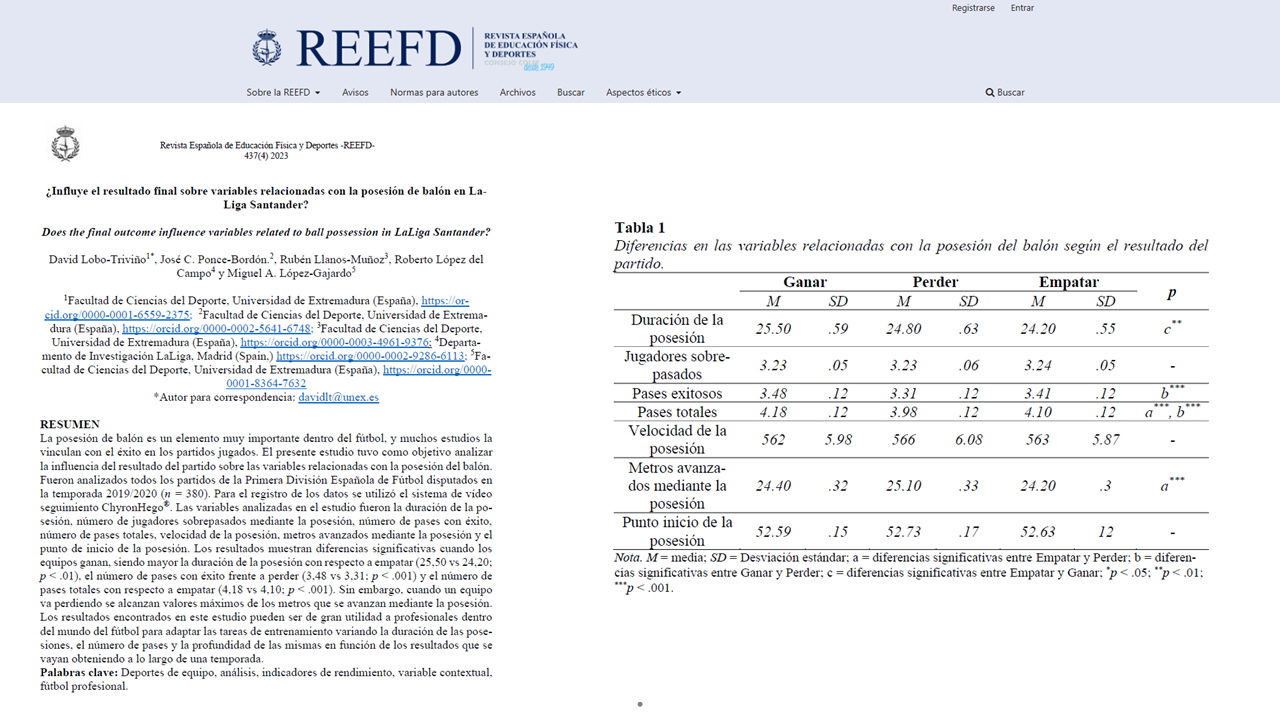

The results challenge some common assumptions in elite football. More possession does not always mean chasing the game. In LaLiga, teams that are winning tend to hold the ball for longer. They complete more passes. They prioritise control. Possession becomes a tool to manage the match rather than to attack relentlessly.

When teams are ahead on the scoreboard, possessions last longer. They include more total passes and more successful passes. This suggests a clear tactical behaviour. Winning teams use the ball to slow the game down, reduce chaos, and limit opponent opportunities. Possession becomes a defensive weapon with the ball, not without it.

This has direct implications for match management. If your team is leading, protecting the advantage is not just about defending deeper. It is about sustaining possession with low risk. Shorter passing options. Fewer forced vertical actions. More patience. The ball becomes the best defensive structure on the pitch.

The study also shows that when teams are losing, possession changes character. Possessions are faster. They cover more metres. Teams try to progress quickly. They push the ball forward with urgency. Verticality increases. Control decreases.

This behaviour is easy to recognise in live matches. Losing teams accelerate circulation. They take more risks. They advance more distance per possession. The objective is clear. Reach the opponent’s goal as fast as possible. Create chaos. Force defensive errors.

For coaches and analysts, this highlights a key point. Possession metrics must always be read through the lens of match status. High possession while losing does not necessarily indicate control. It often reflects urgency. Speed. And risk exposure.

Interestingly, some variables remain stable regardless of the score. The number of opponents bypassed during possession does not change significantly. Neither does the starting point of possession. This suggests that structural build-up zones remain consistent, while what teams do after gaining the ball is what truly changes.

From a training perspective, this study offers very clear guidance. Training tasks should reflect scoreboard realities. If a team struggles to protect leads, sessions should include long possession drills under low-risk constraints. Focus on pass security. Decision-making under reduced pressure. Match tempo control.

If a team struggles to come back from losing positions, training should replicate fast possessions with vertical intent. Short time limits. Mandatory forward progression. High-speed circulation. Players must learn how to attack with urgency without losing collective structure.

For performance staff, these findings also inform physical and recovery planning. Faster, more vertical possessions increase physical stress. They demand more high-intensity actions with the ball. This matters when analysing match load in games where the team spent long periods chasing the score.

For analysts, the message is simple. Possession percentage alone is meaningless. Duration, speed, pass volume, and metres progressed provide the real story. Always contextualise possession by match result. Otherwise, interpretation becomes misleading.

This research confirms a fundamental principle of elite football. Teams adapt their use of the ball to the scoreline. Possession is not a philosophy. It is a strategic response to the game state. Understanding this allows coaches and staff to design better training, manage matches more effectively, and make more informed tactical decisions.