07 Nov Counter-Attack and Progression: The Two High-Sprint Phases that Win Matches

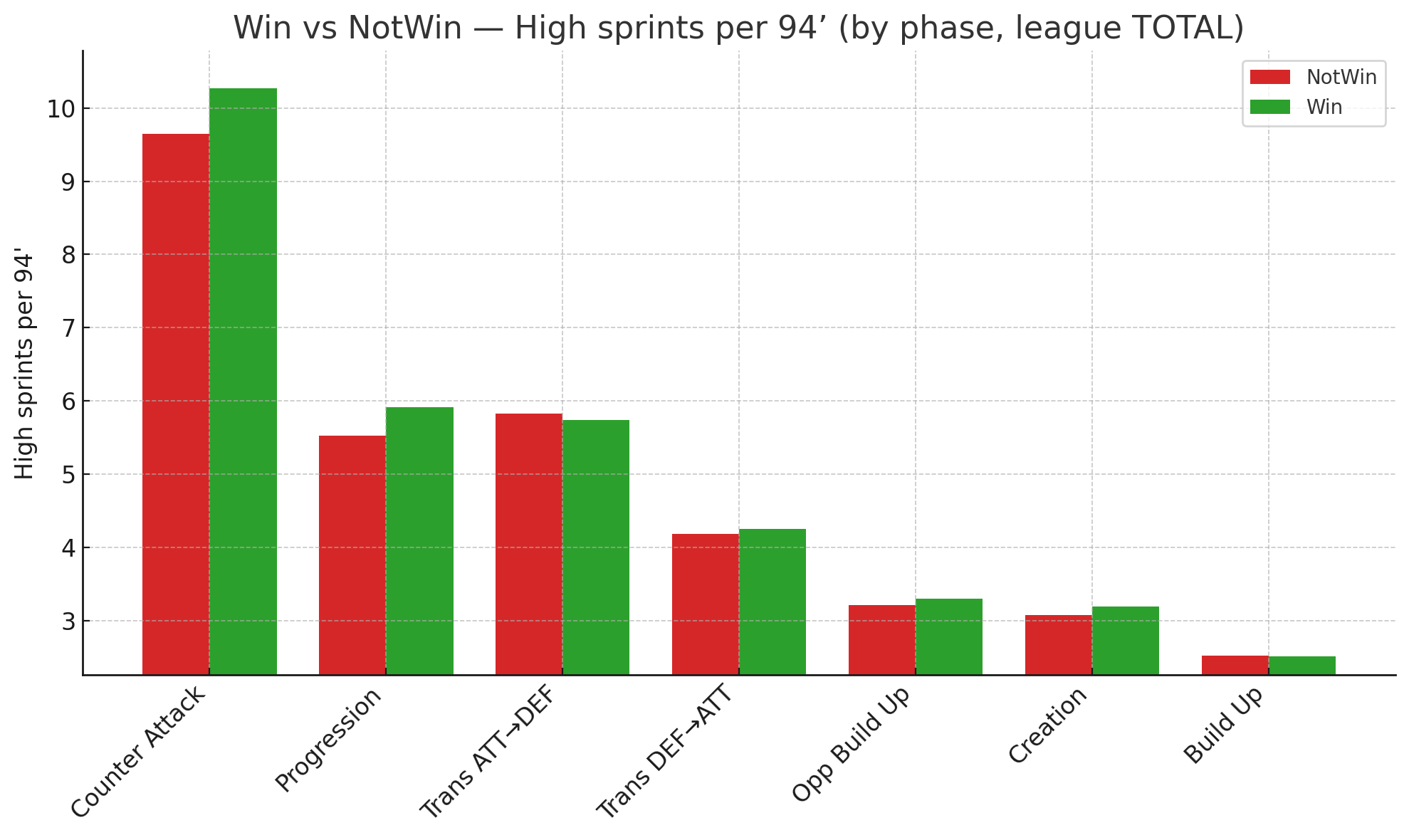

High sprints = running faster than 24 km/h (not just >21 km/h). In LALIGA 24/25, the phases that demand them most are Counter-Attack (No.1) and Progression (No.3)—and the teams that win post more of them.

The moment that decides matches

Minute 70. 1–1. You can press after losing the ball, or you can attack space with pace. Which buys you more wins?

We turned the entire LALIGA EA Sports 2024/25 season into a “living lab” and followed one simple rule: let the data lead. We measured high sprints (>24 km/h) per 94 minutes across the main phases of play and asked: Where do winners actually run hardest—and where should coaches load training?

The big picture (what the league really looks like)

Across the season, if we treat LALIGA as one “super-team”:

- Counter-Attack is the No.1 phase by high-sprint demand (≈ 9.9 high sprints/94’).

- Progression with the ball ranks No.3 (≈ 5.7).

- Transition after loss (ATT→DEF) sits No.2 (≈ 5.8), but here’s the twist: winning teams tend to do fewer of those high sprints by reducing exposure, not by trying to “outrun” the emergency.

And when we compare game by game:

- Winners produce more high sprints in Counter-Attack and Progression than their opponents.

- Total high-sprint volume is also higher in wins (≈ 35.2 vs 33.9 per 94’).

- In wins, the share of ATT→DEF actions tends to drop (≈ −1.3 pp), consistent with better rest-defence and loss prevention.

Translation to the pitch: Winning sides run hardest with the ball—not after giving it away.

Why this matters for coaches and physical trainers

You don’t just need “more running”—you need it in the right phases:

- Counter-Attack: the most demanding phase for high sprints.

- Progression: a top-three phase where the best sides keep breaking lines and arriving with speed.

- ATT→DEF after loss: important to control, but your edge comes from needing fewer emergency sprints, not more.

And there’s a key caveat that helps you plan training loads realistically:

Style determines exposure.

A team that spends more time in Progression will accumulate more opportunities to high-sprint there. Another that lives on regains will collect them in Counter-Attack. The intensity per minute matters—but so does how often you’re in that phase. Your match model shapes your load.

How to turn this into training (simple, practical, game-relevant)

1) Counter-Attack: rehearse speed to space

Design: Start from regain; 6–10 seconds to finish; constrain width/depth so one depth run is mandatory.

Coaching cues: First pass forward if safe; runner from the weak side; final third in <10 s.

What to count: High sprints (>24 km/h) per regain; “high-sprint entries” into the box or behind the last line.

Progression rule: Increase distance and recovery when volume drops below your pre-match target.

2) Progression with ball: trigger & go

Design: Positional game with a trigger (third-man, bounce-out, switch). On the trigger, one wide player must high-sprint to receive behind a line.

Coaching cues: Timing > speed—sell the trigger, then explode.

What to count: High-sprint runs to receive beyond pressure; arrivals in the box after a trigger.

3) Reduce ATT→DEF exposure (win by not needing the emergency)

Design: Possession with two pre-organised lines behind the ball. On loss, track recoveries within 6–8 s and passes allowed.

Coaching cues: Close central lanes before you lose it; stop the first pass out.

What to count: Fewer ATT→DEF high-sprint moments across the game; <2 passes allowed after loss; ≥60% losses recovered inside 8 s.

How to use this in the week (planning loads around your style)

1) Pre-match forecast

- Estimate your likely phase mix for the opponent (more Progression? more Transitions?).

- Set phase-specific high-sprint targets: e.g., Counter-Attack ≥ X high sprints/94’, Progression ≥ Y.

- Set a ceiling for ATT→DEF share (if it creeps up, you’re exposed).

2) Session distribution

- Allocate high-sprint exposures to the phases you expect to need most.

- Keep the “feel” of the game model: a direct side should accumulate more Counter-Attack runs; a build-up side should ensure Progression high sprints from triggers and weak-side arrivals.

3) Matchday management

- If CA/Progression high sprints dip, refresh wide speed or bait pressure to create depth.

- If ATT→DEF share rises, close distances or lower risk in first build-up line.

4) Post-match debrief

- Review where the high sprints happened, not just how many.

- Use that map to set the next week’s load and the individual top-up.

A coach’s checklist for Monday

- Are we creating enough chances to high-sprint in Counter-Attack and Progression?

- Are we preventing emergency high sprints after loss through structure (rest-defence), not just running harder?

- Do our KPIs match our style (phase mix) so training loads reflect the real match?

Methods in one view (transparent and simple)

- Competition: LALIGA EA Sports 2024/25, all matches.

- Definition: High sprint = >24 km/h (not the generic >21 km/h sprint).

- Metrics: High sprints per 94 minutes by phase; totals; phase shares.

- Comparisons: Win vs Not-Win (draw+loss); winner vs loser within the same match.

- Stats: Non-parametric tests with correction and effect sizes.

- Department: Football Intelligence & Performance, LALIGA.

Bottom line

If you want results, plan for high sprints with the ball. Counter-Attack and Progression are where the league spends its fastest efforts—and where winners consistently out-run their rivals. Then organise so you don’t need to high-sprint after losing it.