28 Jul “Do Teams Really Run More Without the Ball? It Depends on How Long They Have It”

What if we’ve been misreading match data for years?

Picture this: your team has 30% ball possession. You press when you lose it, defend in a compact block, and hit hard on transitions. You assume your players are working hardest off the ball. But what if that assumption is wrong?

That was the question we asked at the Football Intelligence & Performance Department of LALIGA, and the answer surprised us.

Because when we analyzed over 8,000 match entries from LaLiga, we discovered that physical effort isn’t determined solely by whether you have the ball—it also depends on how much of the ball you have.

What seemed like a tactical certainty («players run more out of possession») starts to unravel once we factor in possession percentage.

Context: Physical output and possession, a misunderstood relationship

Physical performance metrics are now a staple in elite football. Total distance covered and high-intensity running (over 21 km/h) are used weekly to assess player workload, compare matches, and guide training decisions.

For years, data and literature have agreed on a simple pattern: players cover more distance when they’re out of possession (OP) than when they’re in possession (IP).

But is that always true?

And if not—what’s the missing variable?

That’s what we set out to explore.

The study: Over 8,000 data points, one league, one big question

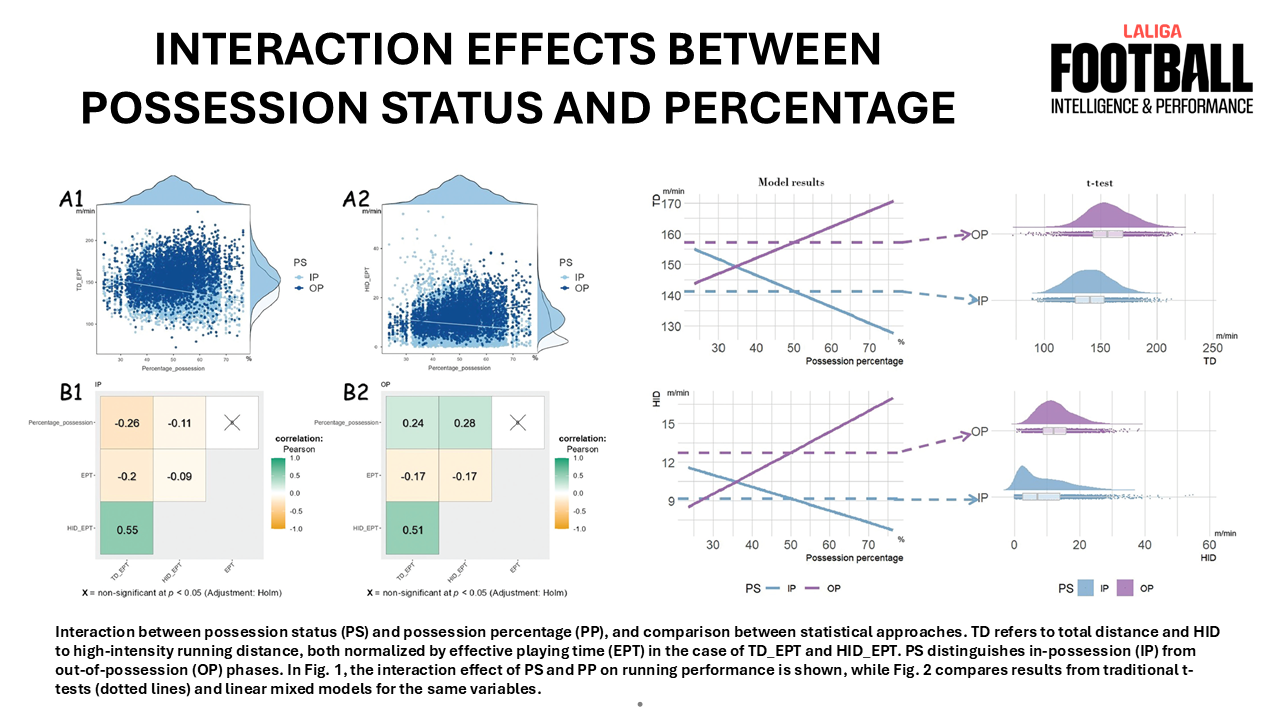

We analyzed 8,468 individual match observations of outfield players from LaLiga’s 2018/19 season. Only full matches without red cards were included to ensure clean comparisons.

Using Mediacoach® and TRACAB® tracking at 25 Hz, we focused on two core indicators:

- Total Distance (TD) per minute of Effective Playing Time (EPT)

- High-Intensity Distance (HID) (> 21 km/h), also normalized by EPT

Crucially, we distinguished between in-possession (IP) and out-of-possession (OP) phases and introduced possession percentage (PP) as a continuous variable in the model.

We also controlled for contextual factors: match location, result, and opponent strength. Linear mixed models allowed us to explore the complex interactions between these variables.

The full paper is available here: https://doi.org/10.5114/biolsport.2025.151653

The key finding: Possession changes the physical rules of the game

What we found challenges the conventional view. Yes, players usually run more without the ball—but only when their team holds possession above a certain threshold.

What’s that tipping point?

- When a team has less than 36% possession, players cover more distance per minute with the ball than without it.

- For high-intensity efforts, the figure is similar: 36.4%.

In practical terms:

Low-possession teams work harder in attack than in defense.

This may seem counterintuitive, but it aligns with what many coaches observe. Teams that defend deep and transition quickly often execute long, explosive attacking runs—overlapping fullbacks, forward sprints, through-ball chases.

Meanwhile, their defensive structure might be more compact, demanding less constant movement.

But here’s an important clarification:

Low possession does not always reflect a tactical decision.

Sometimes teams choose to cede the ball; other times, it’s the result of game context, opponent dominance, or simply a lack of ability to retain possession.

Our model doesn’t measure intention. It only shows that, regardless of strategy, when possession drops below 36%, attacking phases become more physically demanding.

This insight adds a layer of nuance to existing literature. Previous studies have consistently shown that match running performance is higher out of possession, but few—if any—have identified a threshold where that pattern flips. Some authors have examined contextual factors like match status or team strength, while others have explored the effects of formation or ball-in-play time. However, none have demonstrated a turning point in the physical load based on possession percentage, nor have they quantified its interaction with attacking and defending phases using normalized metrics.

Positional differences: Who does this affect the most?

Not all positions are impacted equally. We found distinct thresholds for each role:

- Forwards and wide midfielders only run more out of possession when their team exceeds 68–70% possession. Below that, their offensive workload dominates.

- Centre backs and central midfielders reach that inversion point much earlier—somewhere between 10–30% possession.

These insights can guide more precise training design and performance interpretation by role and team style.

So what does this mean for coaches, performance staff and analysts?

This finding has immediate implications for professional football environments. Here are a few key questions worth asking:

- If your team plays with low possession, are you overloading defensive drills while underpreparing for the actual physical load of attacking transitions?

- When analyzing post-match physical data, are you contextualizing by possession percentage?

- Are you assuming that your highest work rate always comes when out of possession?

- How do you factor offensive high-intensity effort into your microcycle planning?

The key message is: never assume. Context matters. Possession percentage, opponent quality, match status, and tactical identity all shape physical demands.

One honest caveat, without diluting the message

Though this study is methodologically robust (large sample, normalized metrics, multivariate models), it’s worth noting:

- It’s based on a single league and season (LaLiga 2018/19).

- It doesn’t include sprinting, acceleration, or neuromuscular fatigue metrics.

- It doesn’t assess tactical intent—only observed outcomes.

Still, the interaction between PP and possession status (IP vs OP) is both statistically significant and, as far as we know, not demonstrated in any prior study.

That makes this a meaningful contribution—not just academically, but practically.

Listen to the podcast episode

Want to hear how we explain these findings directly to coaches and analysts?

Listen to the podcast episode from LALIGA’s Football Science series here:

Conclusion: Ask better questions. The answers will follow.

How much do your players really run when they attack?

This question might change how you build your training week, interpret your post-match report, or choose between two tactical approaches.

Because the old mantra isn’t always true.

You don’t always run more without the ball.

And when you rarely have it, your attacking effort can be higher than your defending one.

Understanding this nuance might help your team run smarter—not just harder.