15 Abr Impact of Acceleration and Acceleration-Initial Speed Profiles on Team Success in LaLiga

Modern elite football is not decided by who runs the most. It is decided by who accelerates better, more often, and in the right moments. This study analysed two full LaLiga seasons and more than six thousand match performances to understand how acceleration profiles relate to team success.

The key message is simple. Successful teams accelerate more, and they accelerate better. This is especially true in positions that constantly interact with space, pressure, and transitions.

The study focused on two concepts. The first was the number of high-intensity accelerations, defined as efforts above 3 m·s⁻². The second was the acceleration–initial speed profile, which describes how well a player can accelerate from different starting speeds during real match play. This is not a sprint test. It reflects what actually happens on the pitch.

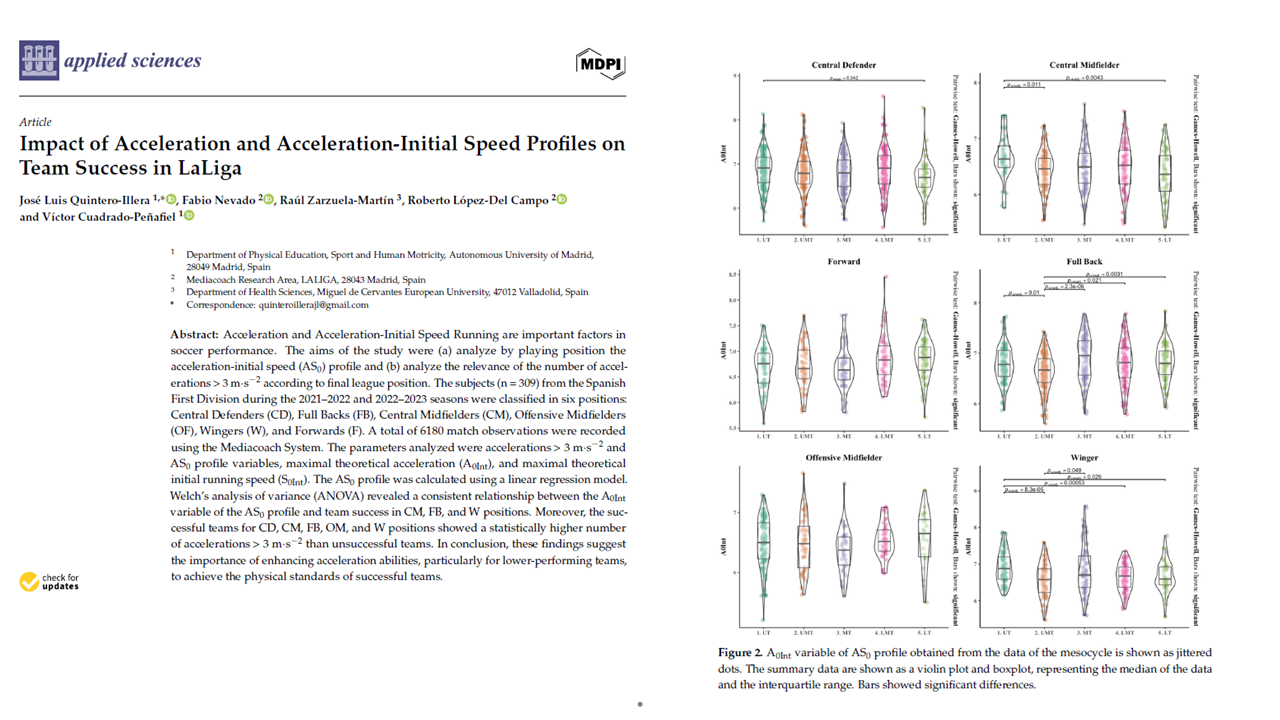

Teams finishing in the top positions of LaLiga consistently performed more high-intensity accelerations than teams at the bottom of the table. This difference appeared clearly in central defenders, central midfielders, full backs, offensive midfielders, and wingers. These roles are deeply involved in defensive reactions, pressing actions, support runs, overlaps, and recovery efforts. Acceleration, not top speed, is what allows these players to arrive first.

One of the most important findings is that maximum speed was not what separated successful teams from unsuccessful ones. The ability to reach very high speeds showed no meaningful relationship with league position. What mattered was how fast players could accelerate from low or moderate speeds. In football terms, this is the difference between reacting first or reacting late.

The acceleration–initial speed profile revealed that players from top teams, particularly central midfielders, full backs, and wingers, showed a higher theoretical acceleration capacity. This means they could produce stronger acceleration even when already moving. These players are better prepared to repeat explosive actions during the match without needing a full stop beforehand.

From a coaching perspective, this changes how physical performance should be interpreted. If a team covers fewer sprint metres but performs more intense accelerations, it may actually be better adapted to the real demands of elite competition. Short, sharp actions decide duels, transitions, and key moments near the ball.

For strength and conditioning coaches, the implications are direct. Training should prioritise acceleration quality over pure sprint distance. Players must learn to accelerate from walking, jogging, and moderate running speeds. Gym work should support horizontal force production, not just maximal power outputs. On the pitch, drills must reproduce frequent accelerations under tactical constraints.

For performance staff and analysts, acceleration counts offer valuable information, but they should not be interpreted in isolation. The acceleration–initial speed profile adds context. Two players may produce the same number of accelerations, but one may do so from much higher initial speeds, reflecting superior neuromuscular capacity and match readiness.

For coaches, this study reinforces that physical performance is not separate from tactical success. Teams that press higher, defend aggressively, and attack with width and depth demand more repeated accelerations. To sustain these behaviours across a season, players must be trained to tolerate and repeat high-intensity accelerative actions.

In simple terms, elite football rewards players who can explode into space again and again. Teams that win are not just faster. They are sharper.

This research provides a clear direction. If a team wants to close the gap to the top of the table, improving acceleration capacity is not optional. It is a competitive necessity.