10 Feb Position Bias

Why comparing football players without respecting their demarcation systematically distorts performance analysis in elite football

Comparing players is a daily habit in professional football.

We compare passes, sprints, accelerations, duels and shots.

Dashboards look clean. Rankings look objective.

Decisions feel data-driven.

But a structural problem sits underneath these comparisons.

A bias that appears before tactics, before roles, before style of play.

A bias that emerges the moment players are compared without respecting their playing position.

This is positional, or demarcation, bias.

Why the comparison is flawed from the start

In elite football, players do not share the same game.

They share the pitch, but not the same problems.

A centre-back and a winger do not operate in the same spaces.

They do not perceive the same affordances.

They do not face the same tempo of decisions.

Yet they are often evaluated through the same KPIs.

The scientific evidence is unequivocal.

Physical performance is position-dependent

Large-scale studies using professional football tracking data from LALIGA show that playing position systematically conditions physical performance across seasons.

Acceleration–speed profiles follow robust positional patterns.

Forwards and wide players consistently exhibit higher acceleration intensity and greater speed expression.

Central defenders present the lowest values and different acceleration characteristics.

These are not individual traits.

They are positional constraints repeatedly documented in elite football datasets

(https://doi.org/10.5114/biolsport.2025.150035, https://doi.org/10.5114/biolsport.2025.151652).

Peak demands show the same structure.

Worst-case scenarios over short time windows reveal that the timing, intensity and shape of the most demanding passages of play differ sharply across demarcations

(https://doi.org/10.3390/jfmk10020172).

From a metabolic perspective, high metabolic load distance also follows a clear positional gradient.

Wide and offensive players are systematically exposed to higher demands than central defenders, across competitive levels and match contexts

(https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.13318).

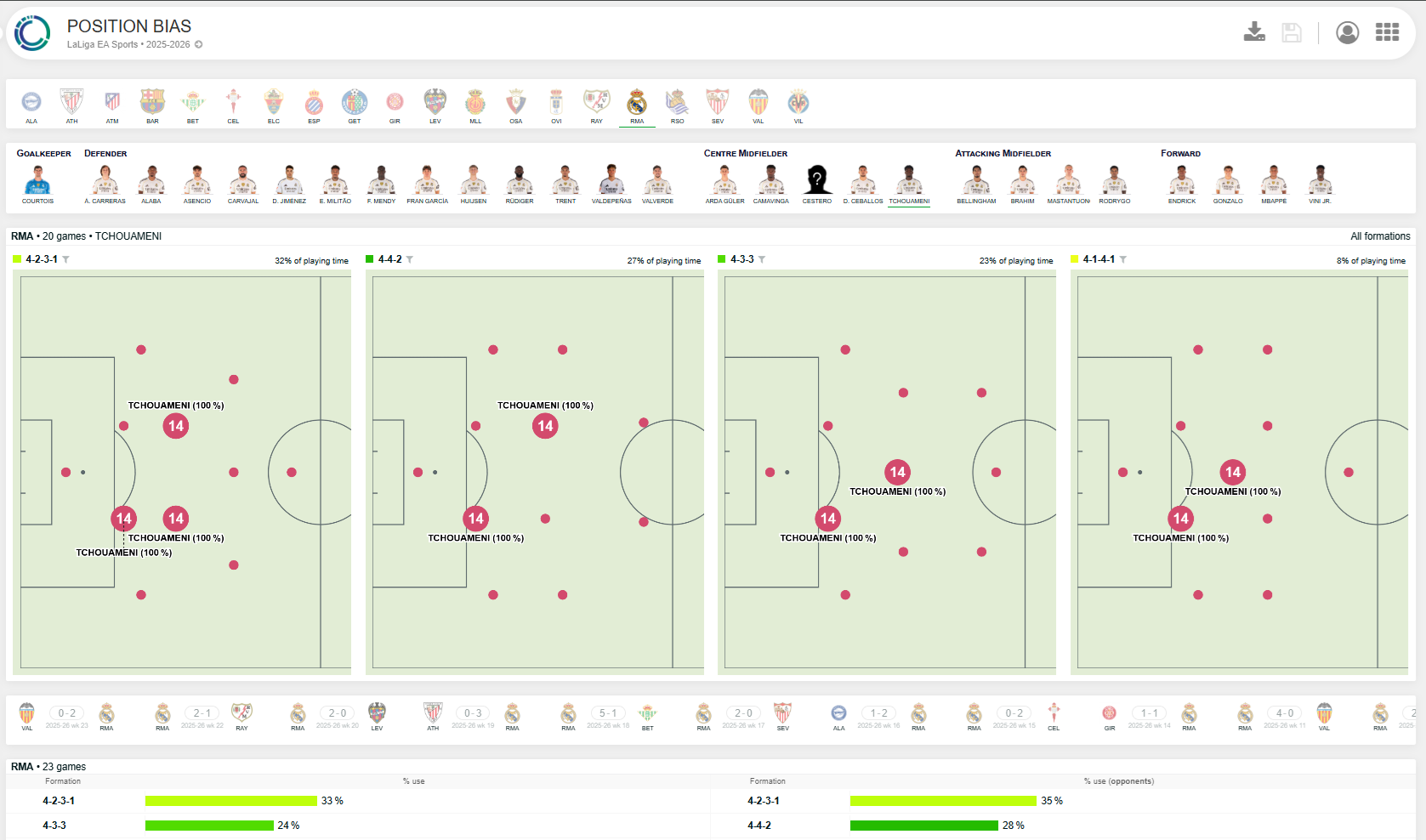

Spatial and tactical behaviour also depends on position

Positional bias is not limited to running metrics.

Proximity-based analyses show that forwards accumulate substantially more close interactions with opponents, while midfielders and defenders operate under very different spatial and tactical constraints.

The space they defend, attack and interact in is structurally different by demarcation

(https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.723414).

This directly shapes tactical behaviour, exposure to duels, and interaction density during competition.

Technical-tactical actions are anchored in demarcation

When physical and technical-tactical performance are analysed together, the same pattern emerges.

Passing volume, forward actions, attacking-zone involvement, dribbles, crosses and recoveries are not evenly distributed across the team.

They follow the logic of positional responsibility.

This has been consistently shown when analysing professional football across divisions and seasons

(https://doi.org/10.5114/biolsport.2022.105331, https://doi.org/10.5114/biolsport.2026.156233).

These differences are not stylistic preferences.

They are the mechanics of the position itself.

Where the bias enters practice

When players are globally ranked on passes, sprints, accelerations or duels, an implicit assumption is made.

That all players operate in the same decision space.

They do not.

Playing position determines where a player receives the ball.

It determines which actions are realistically available.

It determines how often those actions are even possible.

Comparing raw KPIs across positions is not neutral.

It systematically favours some demarcations and penalises others.

This can distort scouting decisions.

It can misguide load management.

It can lead to inappropriate training targets.

This is not a methodological critique

Demarcation labels are not perfect, but they are necessary.

They explain a large proportion of performance variance and make interpretation meaningful.

The problem arises when these labels are ignored in applied environments.

Before discussing roles.

Before discussing styles of play.

Before discussing tactical nuance.

Ignoring demarcation is already a bias.

The core principle

KPIs do not measure quality in isolation.

They measure task execution under positional constraints.

Comparing KPIs is not the same as comparing players.

Not unless those players are asked to play the same game.

Understanding positional constraints is not an academic detail.

It is a prerequisite for valid performance analysis, sound decision-making and effective training design in elite football.