03 Ene Tell me your position and the possession style of your team, and I will tell you your running demands

How much you run in football is not random.

It depends on your position.

It depends on whether your team has the ball.

And it depends on how long the ball is actually in play.

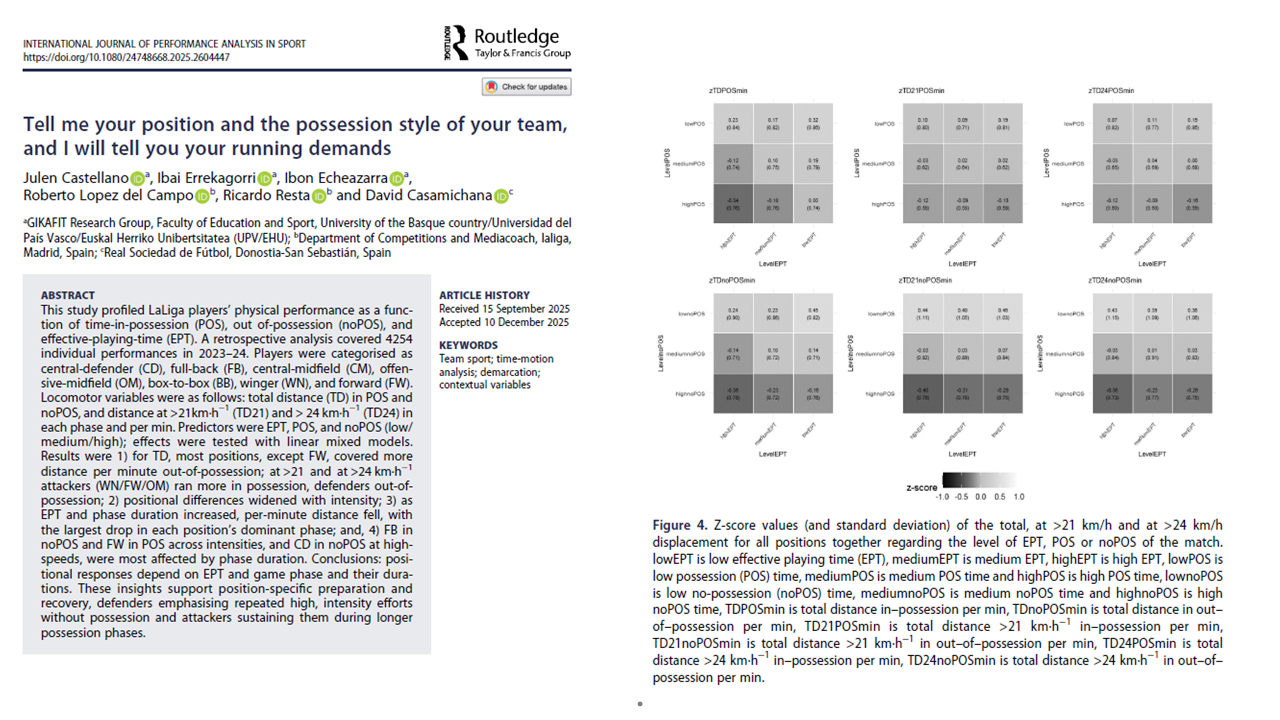

This study analysed 4,254 full-match performances from LaLiga 2023–24, focusing exclusively on effective playing time (EPT) — the real time when the ball is in play — and separating physical demands into in-possession (POS) and out-of-possession (noPOS) phases.

Players were classified into seven positions:

– Central defender (CD)

– Full-back (FB)

– Central midfielder (CM)

– Box-to-box midfielder (BB)

– Offensive midfielder (OM)

– Winger (WN)

– Forward (FW)

Six locomotor variables were analysed:

– Total distance per minute in possession and out of possession

– Distance >21 km·h⁻¹ per minute (TD21) in both phases

– Distance >24 km·h⁻¹ per minute (TD24) in both phases

The results reveal a clear message.

Running demands are not just positional.

They are phase-specific.

And they change depending on possession style and effective playing time.

Total distance per minute

With the exception of forwards, most positions covered more total distance per minute out of possession than in possession.

Central midfielders and box-to-box midfielders showed the highest total displacement values overall, particularly during defensive phases.

Forwards were the only position that systematically covered more total distance per minute in possession than out of possession.

This challenges the simplistic idea that attacking play always implies higher movement demands.

High-speed running (>21 km·h⁻¹)

At higher intensities, positional differences become clearer.

Wingers, offensive midfielders and forwards covered more high-speed distance per minute during possession phases.

Defenders and central midfielders accumulated more high-speed distance per minute during out-of-possession phases.

In other words:

– Attackers sprint more when their team has the ball.

– Defenders sprint more when their team does not.

This contrast sharpens as speed thresholds increase.

Sprint distance (>24 km·h⁻¹)

The pattern is even more pronounced for sprinting.

Wingers and forwards showed the highest sprint values during possession.

Full-backs, central defenders and box-to-box midfielders covered more sprint distance per minute out of possession.

The defensive phase is particularly demanding at high intensities for defenders.

Effective playing time matters

One of the most important findings relates to effective playing time (EPT).

As EPT increases, distance per minute decreases.

This applies across total distance and high-speed metrics.

Longer continuous phases reduce average movement intensity.

The decline is strongest in each position’s dominant phase.

For example:

– Full-backs show the largest drops in intensity during prolonged defensive phases.

– Forwards show the largest drops during extended possession phases.

– Central defenders are particularly affected by long defensive phases at high speeds.

This means physical performance is sensitive not just to phase type, but to phase duration.

Possession style shapes demands

Teams with longer possession phases show lower per-minute intensity in possession.

Shorter possession phases are associated with higher intensity.

Similarly, longer defensive phases reduce per-minute intensity out of possession.

Extreme possession scenarios (very high or very low) reduce physical demand across most positions.

This reinforces the idea that style of play mediates physical output.

Possession-dominant teams tend to show lower running intensity per minute in possession phases.

More transitional or direct matches generate higher per-minute demands.

Positional sensitivity to context

Not all positions respond equally to contextual variables.

Full-backs are highly sensitive to defensive phase duration.

Forwards are highly sensitive to possession duration.

Central midfielders and box-to-box midfielders show more stable physical profiles across contexts.

This suggests that physical preparation should not only be position-specific, but also context-specific.

Training implications

These findings provide practical reference values for:

– Designing small-sided games

– Calibrating training intensity relative to EPT

– Planning recovery strategies

– Anticipating match demands based on expected possession style

Defenders should emphasise repeated high-intensity efforts out of possession.

Attackers should be prepared to sustain high-intensity actions during long possession phases.

Substitution decisions during matches may also benefit from understanding which positions are most affected by prolonged phases.

The broader message is clear.

Physical performance in football cannot be interpreted without context.

Tell me your position.

Tell me your team’s possession style.

And I can predict your running demands.